Beginnings (up to 1538)

We know very little about the first church to be built on this site, but by the twelfth century, St Mary’s was at the heart of the growing medieval university. The students and academics of the university gathered in St Mary’s for special occasions such as the awarding of degrees, as well as for services. When the university as a whole needed to make decisions, all the academics – so-called members of Congregation – would meet in St Mary’s to vote on important matters. The oldest part of the church that remains is the tower, begun in the 1270s. The decorated spire was added in the early fourteenth century and is one of Oxford’s best-known landmarks.

As the university grew, the need for a proper library became evident. St Mary’s was the obvious place to keep the books; they would be safe but could still be read. There wasn’t much space in the church itself, so in 1320 plans were drawn up for a new building next door. It was to have a library on the first floor, and on the ground floor a new room for meetings of Congregation. The library remained here until 1488, when the University finished the new Duke Humphrey’s Library (the oldest reading room in the Bodleian Library) to house its growing collection. Meanwhile, Congregation continued to meet here, in what is now the church cafe, until 1640, when a new Convocation House was built next to the Bodleian.

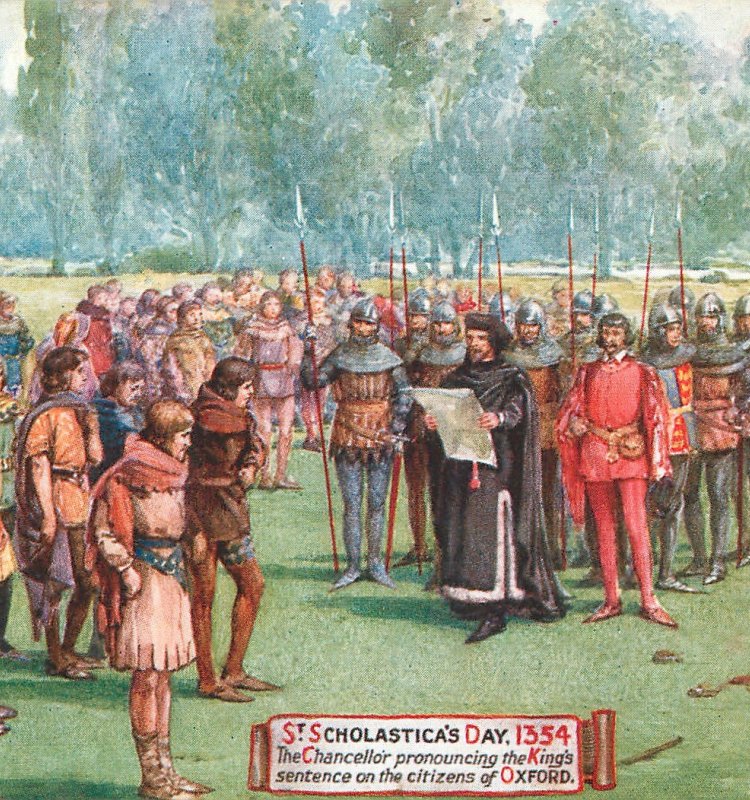

Town and gown both came to St Mary’s, but there was often friction between them. Sometimes the situation got out of hand – and with fatal consequences on one notorious occasion. In 1355, some students complained about the ale in an Oxford tavern, and in a situation already tense with distrust between townspeople and the university, this became the excuse for a pitched battle between armed groups. The scholars came off worse with 63 of their number killed. But the University forced the town to make amends, and every year – on St Scholastica’s day, 10 February – the mayor had to march barefoot to St Mary’s to pay a fine.

The many activities of medieval church life put great strain on the building, and by the late 1400s it was starting to crumble. Thanks to some shrewd fundraising, the chancel was rebuilt in the 1460s with wooden stalls arranged in the style of a college chapel. The nave, however, was still in a very bad state. Rain regularly came through the roof, and people avoided the church in storms because they feared the old beams might fall on top of them! The University and its friends rebuilt the whole nave in the fashionable ‘Perpendicular’ style of the day, with clean straight lines and plenty of light. A stone pulpit was set up in 1508 so that sermons could be heard more easily and a ‘paire of organs’ was also installed. By 1510 the building work was complete, and the University officials could breathe a sigh of relief. Little did they know what great upheavals awaited them.