Restoration and Oxford Movement (1660-1900)

After the turbulence of the Reformation and civil war, the people of the eighteenth century were wary of strong religious feelings. They aspired to be reasonable and ‘polite’ (a fashionable compliment) – no one wanted to be called an ‘enthusiast’. Some churchmen were disappointed by the cold, seemingly complacent faith they saw around them and wanted to reawaken a sense of religious commitment. John Wesley was especially keen to revive the Church and his heartfelt, passionate sermons drew large crowds up and down the country. He was invited to preach at St Mary’s three times; his last sermon, in 1744, was such a powerful attack on the University’s spiritual apathy that he was never asked to return. Undeterred by the reaction of Oxford, Wesley continued his ministry and the movement he founded became the Methodist Church. It was not until nearly a century later that Oxford was ready for spiritual renewal.

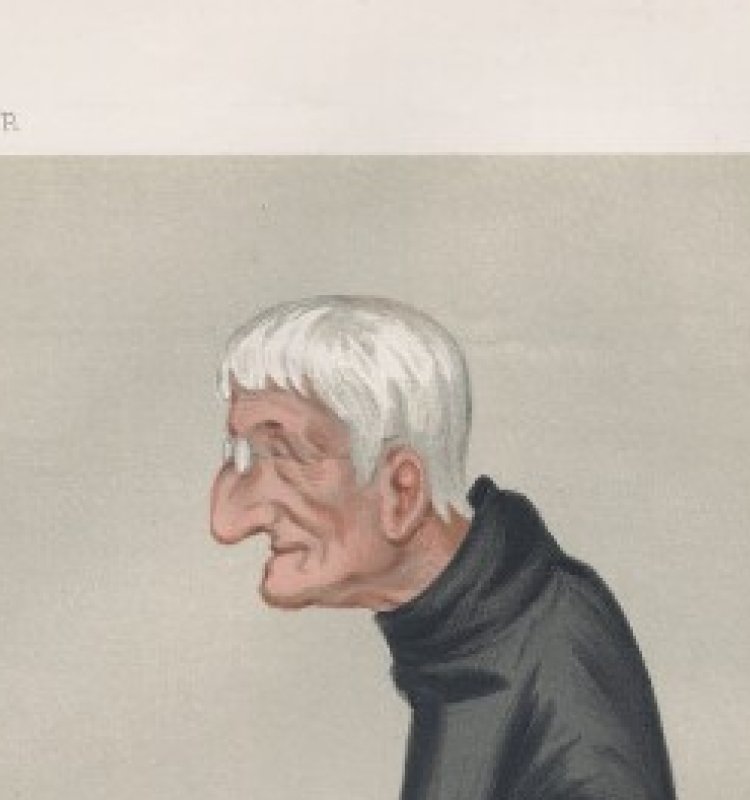

The early years of the nineteenth century saw a rapid rise in undergraduate numbers, and space was at a premium in the church during important sermons and ceremonies. To ease the over-crowding, the University installed new galleries for the undergraduates, on the West and North sides of the church. (The West gallery is still here.) They also provided a new pulpit, raised above the nave so that the undergraduates could hear sermons more clearly. The work was completed in 1827, and the next year Oriel provided the church with a young vicar, a promising Fellow of the college called John Henry Newman. Newman would take advantage of this great opportunity, and his ministry at St Mary’s would have a profound impact – not only in Oxford but on the whole Church of England.

Newman was a man of great seriousness of purpose, worried that the Church was being squeezed out of national life, as public and political life began to be opened up to those outside the Anglican Church. He called for a revitalisation of the Church and a strengthening of its role in society, as the sacred body of Christians past, present and future. Eventually he decided that only the Roman Catholic Church could trace itself back to the time of Christ, and in 1845 he converted to Catholicism. Most of his friends, however, remained in the Church of England. They believed that it was part of the ancient Church begun by the Apostles, and they wanted to renew the Church of England, not abandon it - the ‘Oxford Movement’ soon swept across the country. Thanks to Newman and the Oxford Movement, churches were adorned once more, with stained glass and with intricate decorations.

It was not only the building which was restored; the life of the church was also revitalised in the Victorian and Edwardian period. At St Mary’s, some of the leading philosophers and clergymen of the day set out to dispel the fears of many contemporaries and to show how science and scholarship could strengthen rather than diminish faith. One of the most successful was Frederick Temple, Bishop of Exeter; in a series of Bampton lectures at St Mary’s in 1884 he argued that new scientific ideas (especially Darwinism) were easily reconciled with religious belief. Temple, like the best clerics of his generation, knew that the Church could not avoid hard questions but had to show how its principles were still relevant in their own time. Faith needed understanding, and science should be seen as an ally not an enemy.