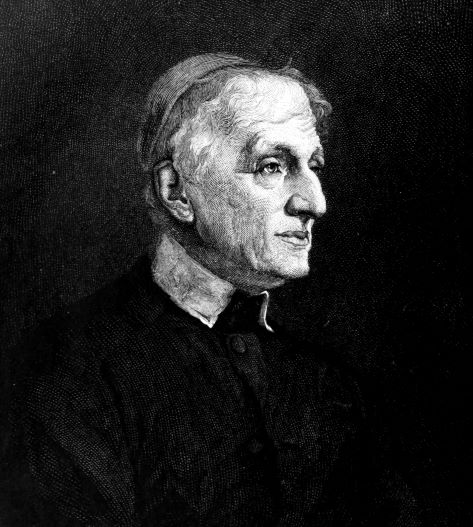

John Henry Newman was born in London on 21 February 1801, the son of John Newman, a banker, and Jemima (née Fourdrinier), of Huguenot descent. It was a prosperous upbringing: the Newmans lived in Southampton Street, Holborn, and Newman and his brothers were sent to board at Ealing School, a rising institution with a growing reputation. In 1816, his father’s bank crashed, precipitating ‘a great change of thought’: Newman’s evangelical conversion.

Having been brought up to delight in the Bible, but having ‘no formed religious opinions’, he now devoured Anglican evangelical classics under the tutelage of his teacher, the Reverend Walter Mayers. Joseph Milner’s ecclesiastical history inspired a lasting love of the Church Fathers, while Thomas Scott – ‘to whom (humanly speaking) I almost owe my soul’ – provided him with two lifelong maxims: ‘Holiness rather than peace’ and ‘Growth the only evidence of life’.

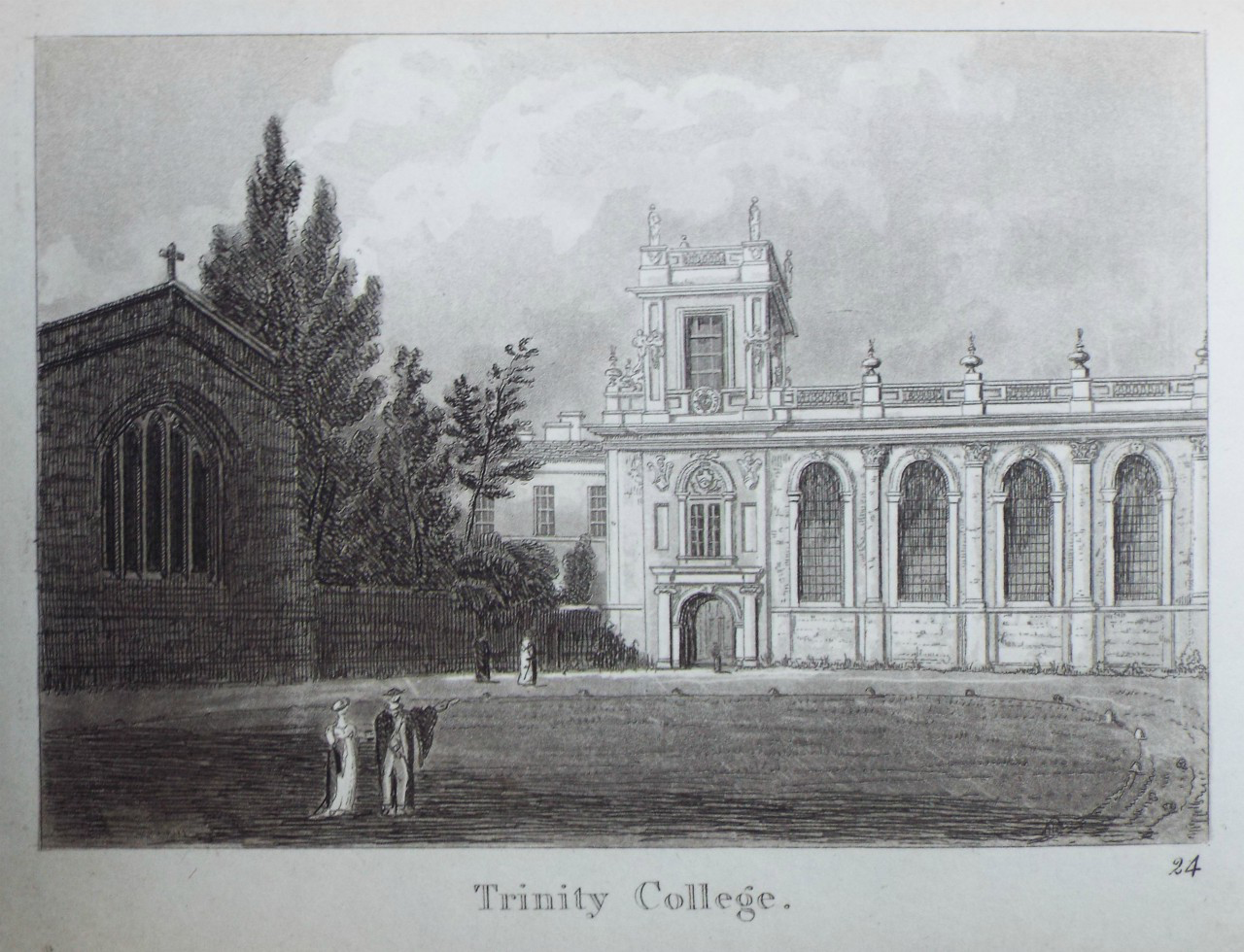

From Ealing he went to Trinity College, Oxford. A disappointing examination performance in 1820 and his father’s bankruptcy in 1821 led him to think seriously about his future. He resolved to take Holy Orders and to read for a fellowship. From the mid 1820s, Newman began to move away from his youthful opinions, but he never repudiated this as the ‘beginning of divine faith in me’.

Dr Gareth Atkins

Queens’ College, Cambridge

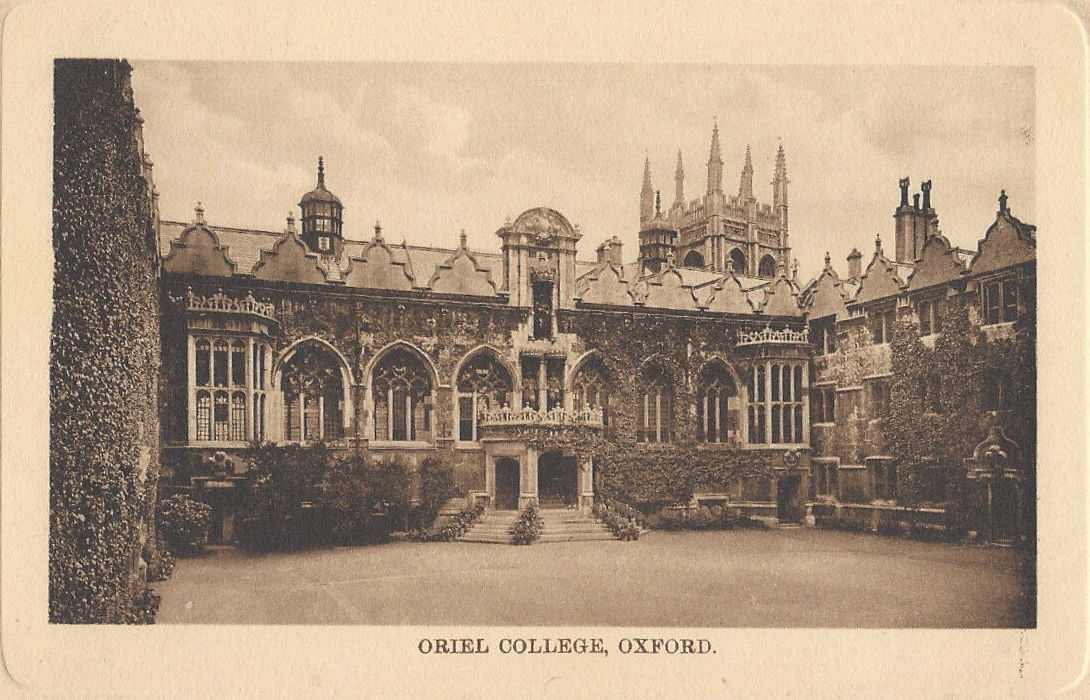

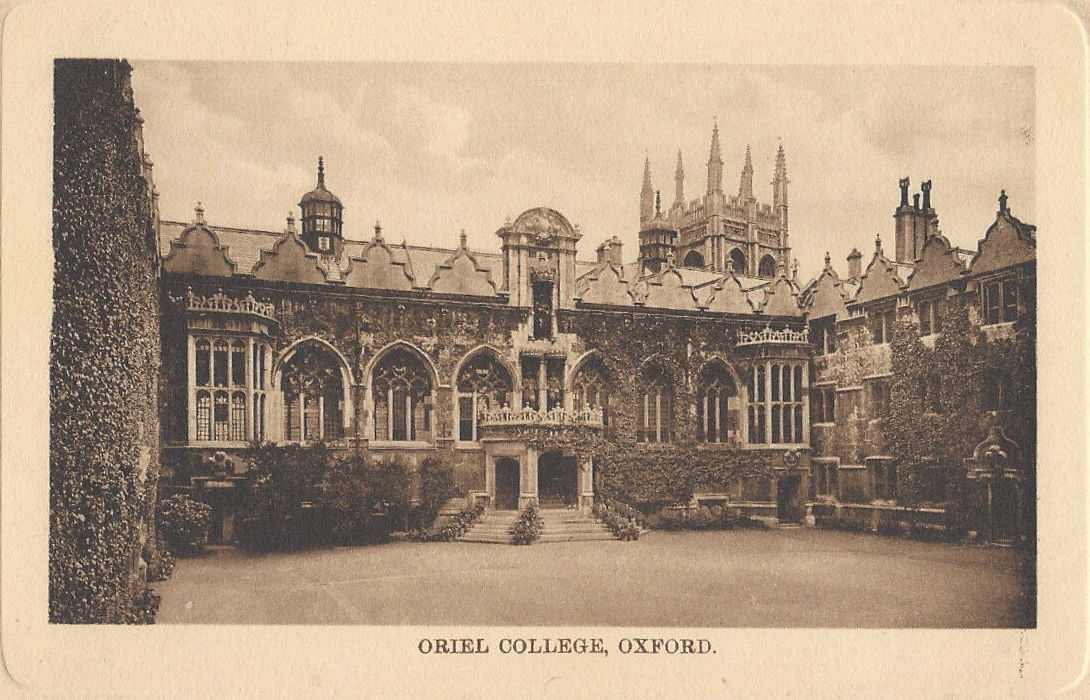

John Henry Newman was a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, from 1822 until 1845. The story of Newman at Oriel represented a major dimension of his spiritual pilgrimage and intellectual development. As he himself later recorded, he ever felt the day of his election as Fellow of Oriel on 12 April 1822 ‘to be the turning point of his life, and of all days most memorable. It raised him from obscurity and need to competency and reputation’.

In that era, Oriel was the most academically and intellectually prestigious of all the Oxford colleges. Newman’s intellectual formation among the Oriel Noetics (proponents of free enquiry) engaged in a rational defence of Christianity against the challenge of heterodoxy and unbelief. They also influenced his religious evolution from an early Calvinist Evangelicalism to something resembling a high church theological understanding of Christianity. Oriel furnished him with the tools and weapons which he employed so effectively as inspirer and leader of the Oxford Movement.

Oxford’s and Oriel’s tutorial system lent itself to Newman’s view that as a college tutor, he held a pastoral office. It proved to be the ideal medium for his emphasis on the importance of personal influence and principle of personality in fostering personal holiness as well as academic excellence. It helped mould his conviction that education involved a moral and spiritual grounding as well as mere intellectual attainment.

Dr Peter Nockles

John Rylands Library

University of Manchester

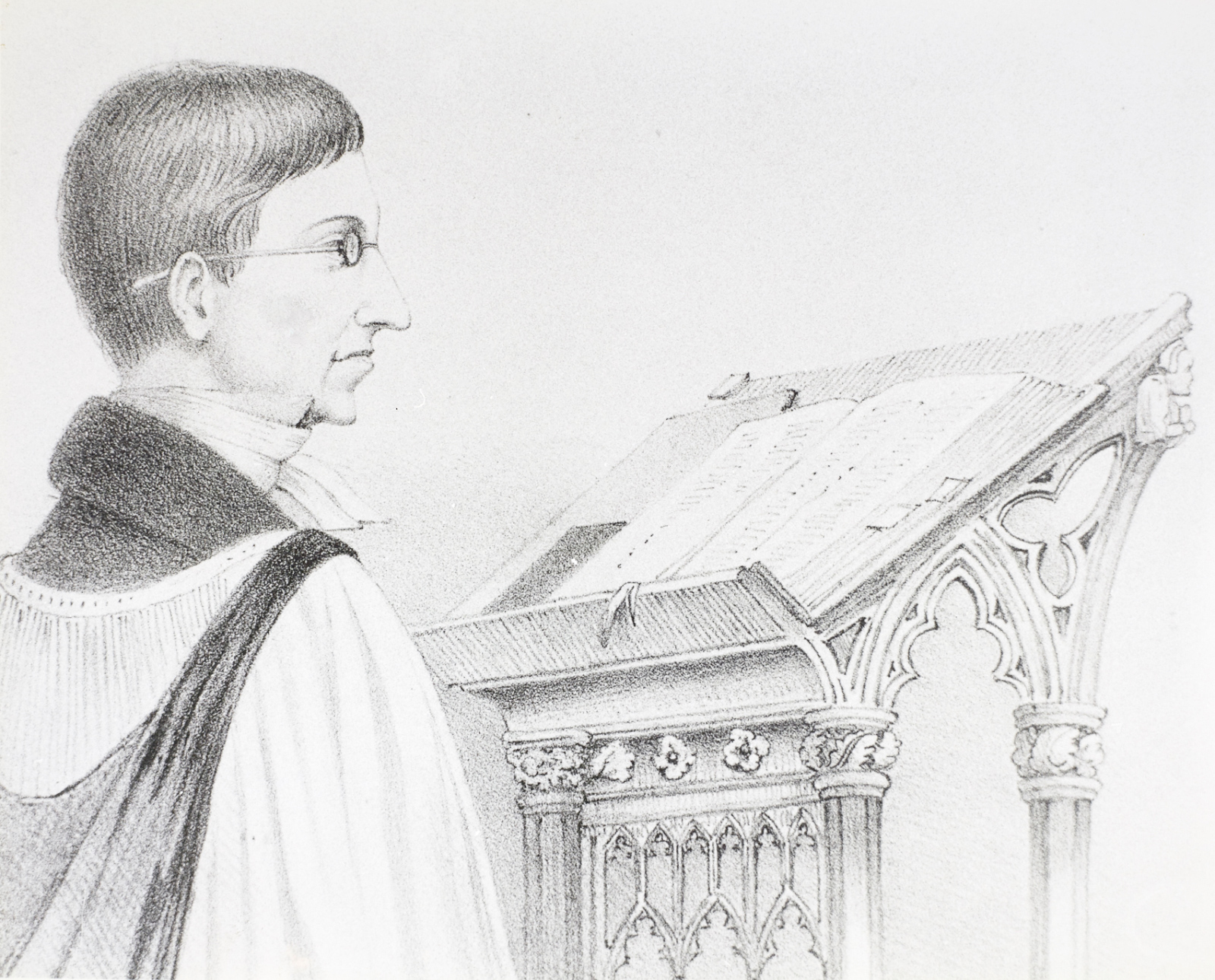

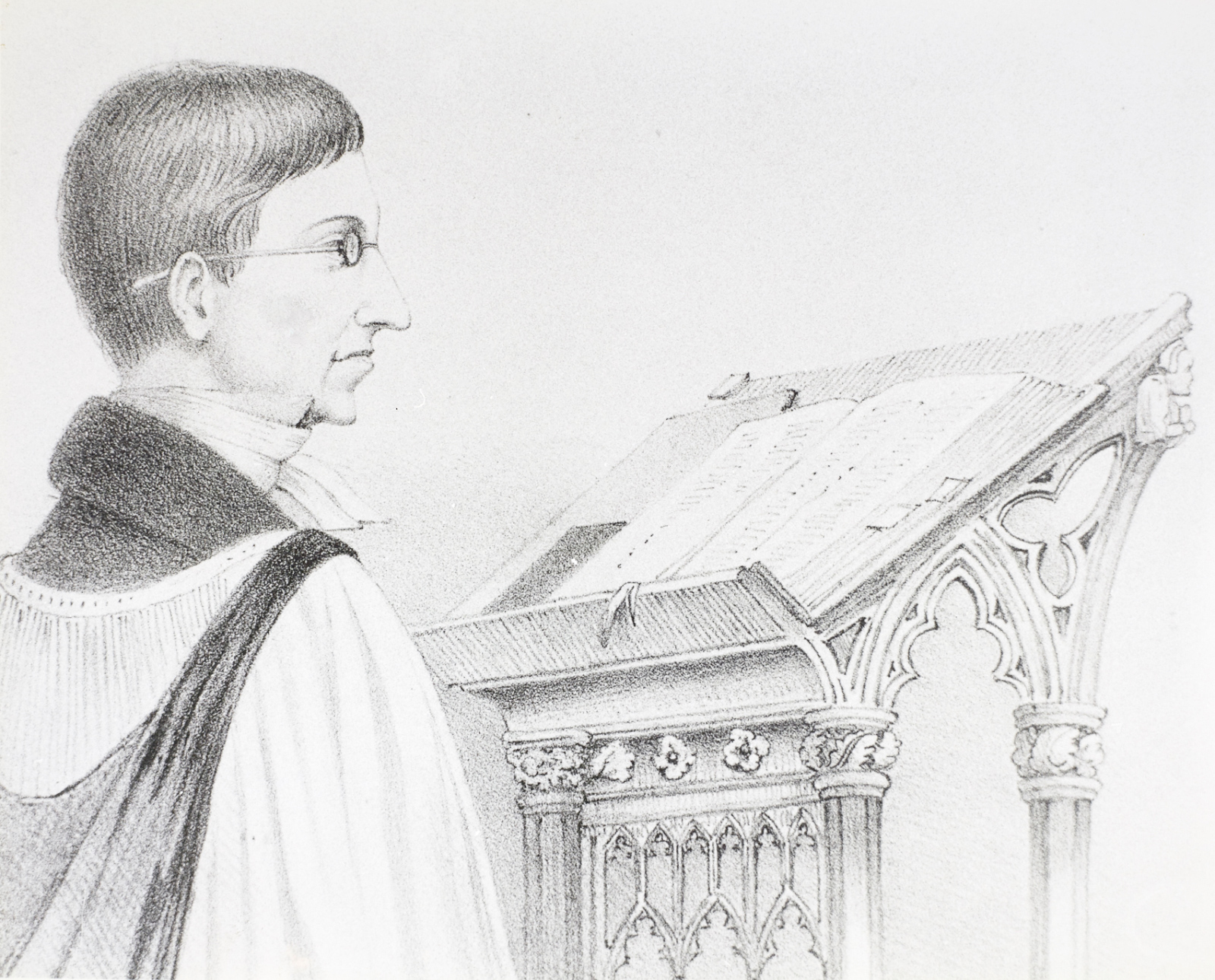

John Henry Newman became Vicar of St. Mary’s in March 1828. The office was at that stage still customarily held by a Fellow of Oriel, it being in the college’s gift as Patron of the living. Newman found himself with so much work on his hands that time for study, not least of the Church Fathers, became scarce. From the University pulpit he nevertheless soon established himself as one of the most compelling preachers in England, although his style and choice of subjects caused controversy in some quarters. In 1833 John Keble preached from the same pulpit his now-famous Assize Sermon on ‘National Apostasy’, which Newman later considered to have been the beginning of the Oxford Movement proper. He agonised about leaving St. Mary’s in the wake of the furore over Tract 90. In the end he resigned in September 1843 and retreated to Littlemore, two years before his reception into the Roman Catholic Church.

Dr Serenhedd James

Oriel College, University of Oxford

The Oxford Movement, also known as ‘The Tractarian Movement’, began at Oxford University in 1833. It intended and effected spiritual, doctrinal, and liturgical renewal in the Church of England by returning to the church fathers and seventeenth century Anglican theologians. In pamphlets and treatises, such as ninety ‘Tracts for the Times’, in sermons, poetry, lectures, translations, hymns, biographies and novels, it relentlessly attacked the university’s, church’s and country’s secularism (religious indifference), liberalism (the view that reason alone cures evil) and Erastianism (final authority in religion belongs to the state). Affirming doctrine and devotion, the Movement promoted the Holy Catholic Church as supernatural and divinely authorized, a visible unity on earth sustained by the grace of the sacraments and the unbroken apostolic succession of bishops.

Its founders, ordained fellows of Oxford’s Oriel College, were noted for their intellectual, moral, and spiritual stature: John Keble (1792-1866), poet of Anglican devotion; Richard Hurrell Froude (1803-1836), zealous apologist for Catholic truths; and Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800-1882), saintly, erudite aristocrat. John Henry Newman (1801-1890) became the acknowledged leader and genius of the Movement. Reaching its zenith in 1838, the Movement, though anti-papal, was increasingly attacked by church and university for resembling Romanism. Nonetheless, it survived Newman’s 1845 conversion to Rome and continued to influence the shape and direction of the Church of England.

Mary Katherine Tillman

Professor Emerita, Program of Liberal Studies

University of Notre Dame, Indiana

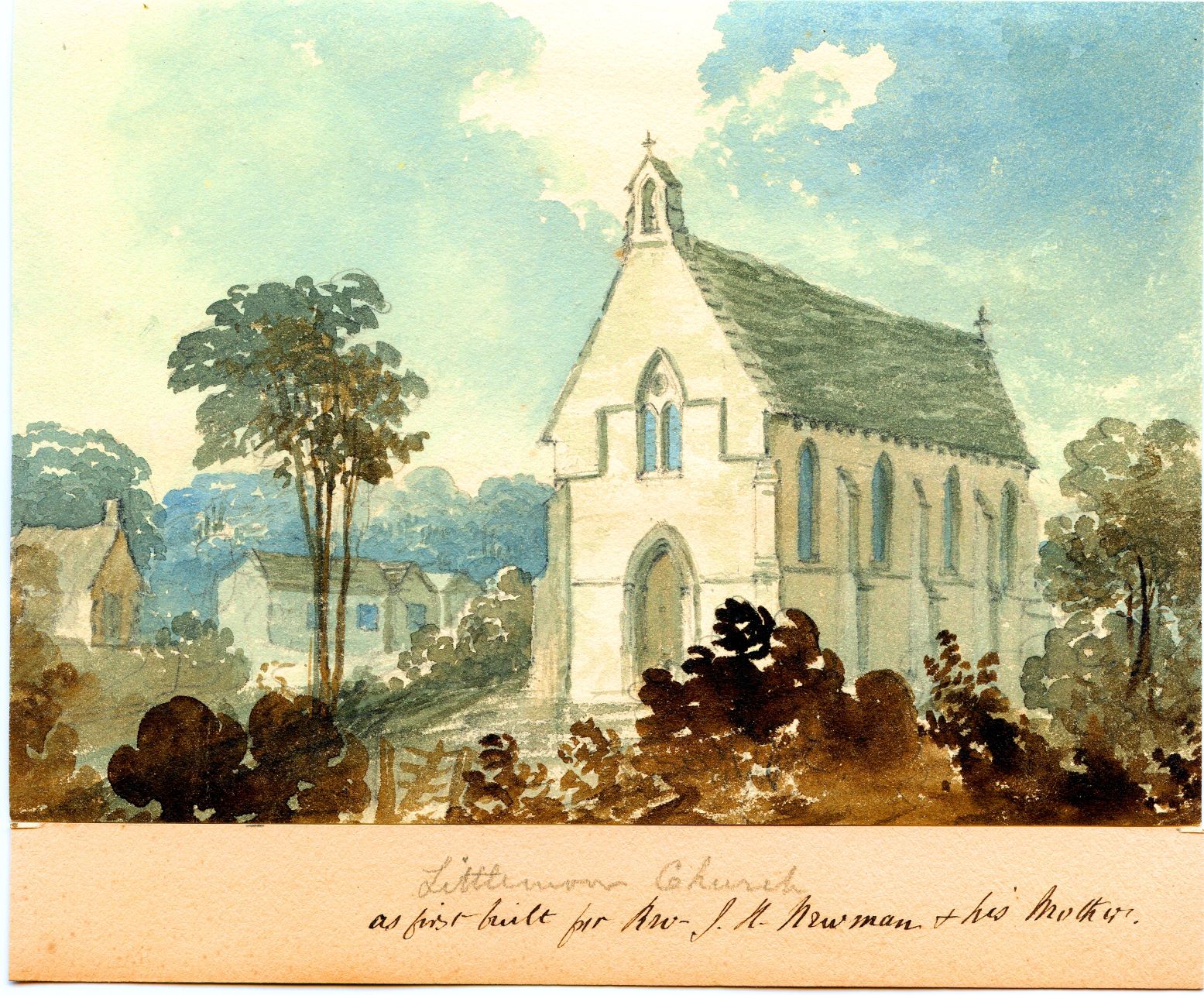

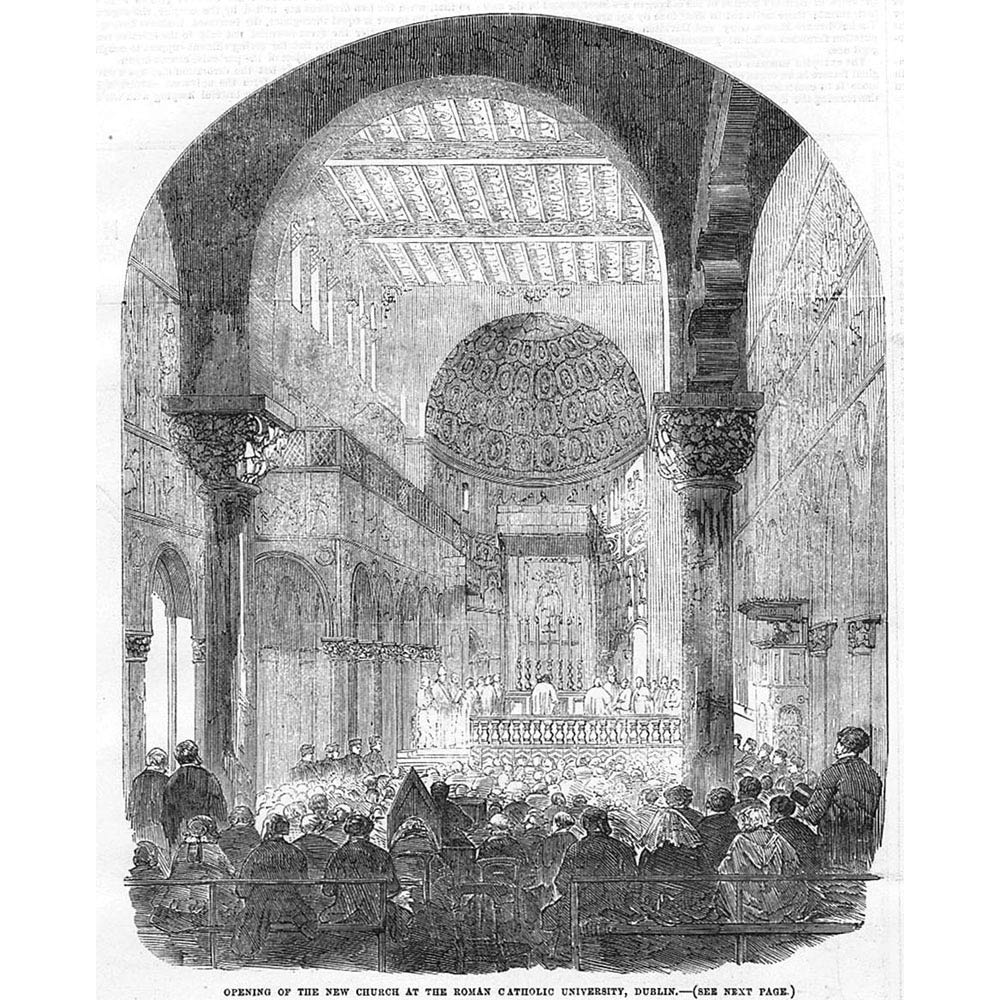

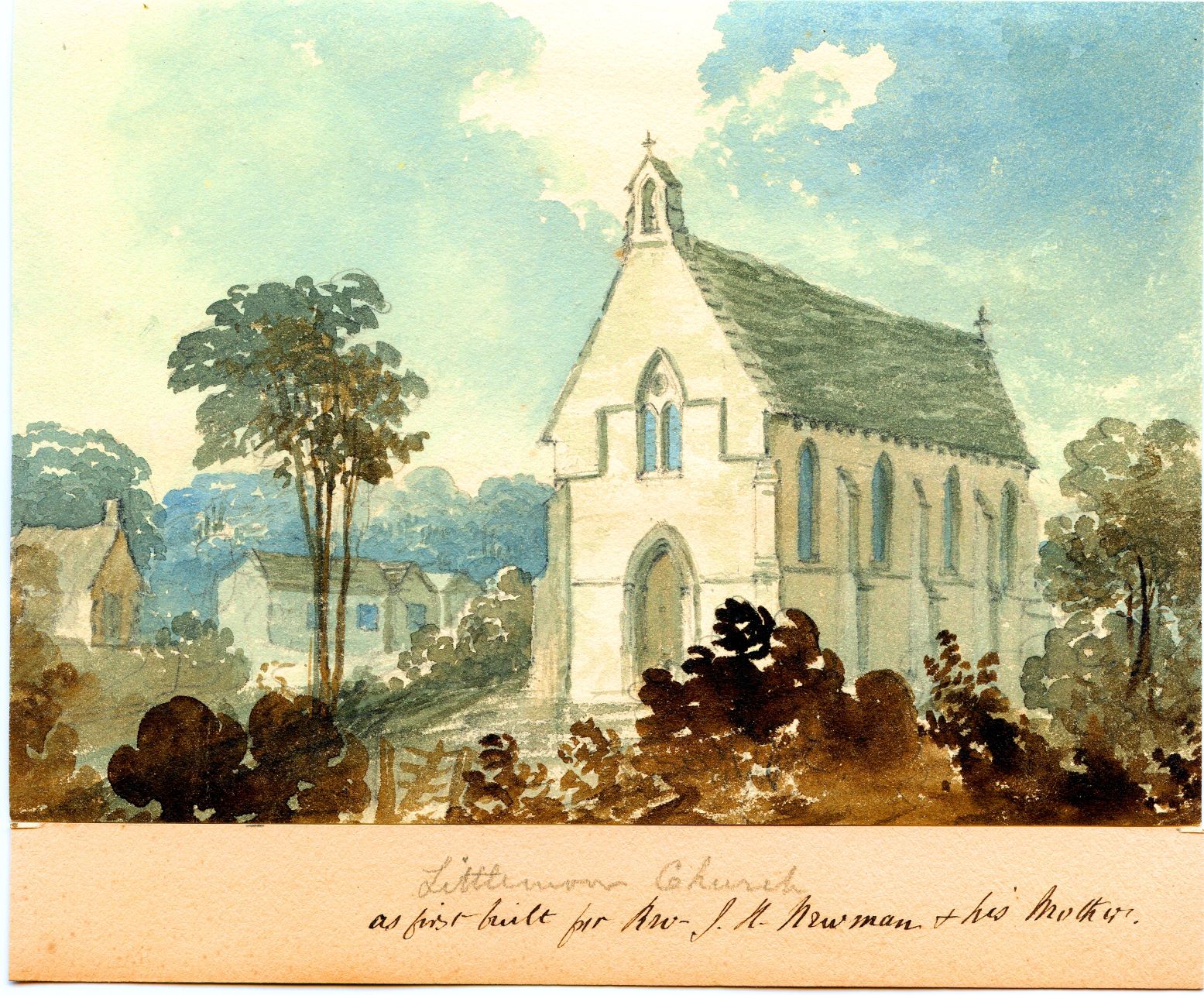

On becoming Vicar of the University Church, Newman discovered that its benefice included Littlemore, an impoverished hamlet 3 miles outside Oxford, with no church of its own. He began to walk there regularly, visiting its rural workers and setting up school lessons for children. His mother and sister helped with pastoral care. In 1835 he secured permission and funding for a church.

Built to Newman’s personal design, with ‘Catholic’ features that shocked many Anglicans, Littlemore Church soon became a model for small elegant places of worship throughout the world. Newman told his parishioners to view its architectural symbolism as ‘a holy book, which you may look at and read, and which will suggest to you many good thoughts of God and heaven’.

Newman’s other legacies in Littlemore included tree planting, building a school and securing land for new resident philanthropists. By 1840 he was staying there regularly and began planning a monastic retreat or ‘college’. He moved permanently into ‘The College’, a converted granary and stables, with a group of like-minded theologians in April 1842. It was here that he famously converted to Roman Catholicism in October 1845, two years after resigning his Anglican duties.

Dr Philip Salmon FRHistS

History of Parliament Trust

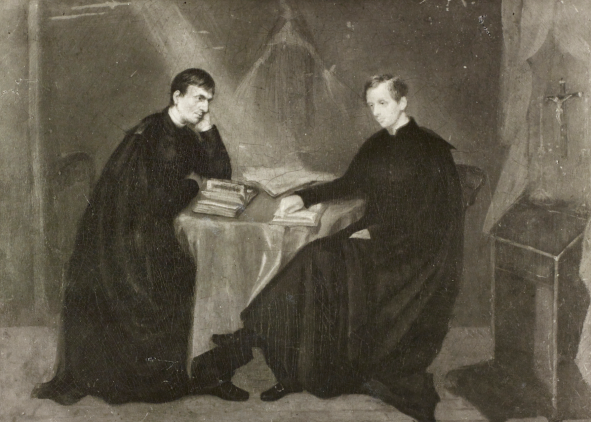

The early 1840s marked a watershed in Newman’s life. As a fellow at Oriel College and leader of the Tractarians, Newman’s influence among Anglicans was near its apex. Yet controversies surrounding Newman’s work precipitated his estrangement from the Church of England and movement toward Rome. In January of 1841, Newman published Tract 90, which attempted to harmonize the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles with the Decrees of the Council of Trent. Swift denunciations of the Tract from leadership in his own Church came as a shock.

In September 1842, Newman retreated from Oxford to Littlemore, where he stayed for his remaining days as an Anglican. There, his views toward Rome continued to take shape. In February 1843, Newman preached his final University Sermon, ‘The Theory of Developments in Religious Doctrine’, which proposed a vision of Christian teaching that changed and expanded through time. This theory became a pillar of Newman’s thought as a Roman Catholic.

In his final months as an Anglican, Newman composed his famous Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, which offered a rationale for his decision to enter the Roman Catholic Church. The Essay stands as a testimony to this turning point in Newman’s life, illustrating how much ecclesial controversy also represented his personal struggle of faith.

C. Michael Shea

Seton Hall University